Echoes of Tattered Tongues: Memory Unfolded

by John Z. Guzlowski

Aquila Polonica, Los Angeles, CA 2015

Some books take a lifetime to write, yet they can be read in one sleepless night, filled with tears of compassion and a heaviness of heart. John Z. Guzlowski’s book of poetic memoirs is exactly such a book: an unforgettable, painful personal history, distilling the horrors of his parents’ experiences in German labor and concentration camps into transcendent artwork of lucid beauty. Called “a searing memoir” by Shelf Awareness, one of the leading book industry media outlets that highlighted the book trailer on their site, Echoes of Tattered Tongues takes the reader on a journey back in time, from the retirement years in Arizona in Book I: Half a Century Later to the life of Displaced Persons in Chicago in Book II: Refugees, and the crucial period of imprisonment in German camps in Book III: The War. It is only through this gradual unveiling of the depth of suffering inflicted on Guzlowski’s mother and father, that we become aware of the historic forces that forged their fates, brought them together, and impacted their son so severely that he spent the past thirty years obsessively writing about his parents’ war-time ordeal and its post-war consequences, as if there were no other topics worthy of his pen.

Born in a refugee camp in Germany, Guzlowski came to America with his parents in 1951 as a Displaced Person: “When we landed at Ellis Island we were unmistakably foreign… We were regarded as Polacks – dirty, dumb, lazy, dishonest, immoral, licentious, drunken Polacks. I’ve felt hobbled by being a Polack and a DP, Displaced Person. It was hard karma.” (“Preface: Where I’m Coming From”).

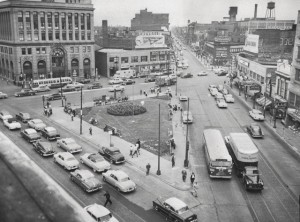

Polish Triangle in Chicago, where the author grew up

A poet, writer and retired professor (Eastern Illinois University), Guzlowski has enjoyed 40 years of a successful academic and literary career, publishing in such journals as North American Review, Ontario Review, Rattle, Atlanta Review, Nimrod, Modern Fiction Studies, Polish Review, and other journals here and in Europe. His poems about his Polish parents’ experiences in Nazi labor and concentration camps were first published in the Language of Mules (DP Press), praised by Czesław Miłosz as “exceptional… astonished me. Reveals an enormous ability for grasping reality.” The heartrending story continued to unfold in the following two books of poems, Lightning and Ashes (Steel Toe Books) and Third Winter of War: Buchenwald (Finishing Line Press). Third Winter was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry; I feel honored to have published the ethereal, snow-filled “A Good Death” in the Chopin with Cherries anthology (Moonrise Press, 2010). A poem from Lightning and Ashes, “What my Father Believed,” appeared on Garrison Keillor’s The Writers Almanac and in Echoes (Book I: Half a Century Later):

“He knew living was hard,

and that even children were meant to suffer. […]

My father believed we are here to lift logs

that can’t be lifted, to hammer steel nails

so bent they crack when we hit them.

In the slave labor camps in Germany

he’d seen men try the impossible and fail.”

In narrative fragments and stark, simple poems, Guzlowski explains his father’s obsessive recounting of his terrible experiences (he spent four years as a prisoner in Buchenwald Concentration Camp and came to America with a trunk made from planks from a barrack’s wall) and his mother’s withdrawn, resigned silence, that she was willing to break only at the end of her life (“My Mother Reads my Poem ‘Cattle Train to Magdeburg’”):

“You think we were bad women

but we weren’t. We were girls

taken from homes, alone.

Some had seen terrible things

done to their families.

Even though you’re a grown man

and a teacher, we saw things

I don’t want to tell you about.”

John with his mother and sister

It took years, Guzlowski writes, for his mother to tell him some of the things she was hiding. Four years before her death, after reading the Polish translation of the Language of Mules, where her story was recounted in hearsay, as retold by her husband, she “looked at me and said: ‘That’s not the way, it was.’” (“Epilogue”). Then, she proceeded to tell her son, “How her Mother and Sister Died”, and how they were buried, along with the murdered baby, in “the marshy grave where the hungry men / Dropped them after shooting them / And cutting them in secret places.” [This crucial story is so important that it deserved retelling in another poem, entitled simply “Here’s What My Mother Won’t Talk About.” She also talked about being raped as a girl of nineteen; explained the train ride to Germany after being captured; and revealed the hunger on the German farm, and the hopeless life of “Sisters in the Labor Camps”:

“They ate,

what the Germans

gave them

soup that was always

too thin, meat alive

and gray

with maggots,

bread made of sawdust

and sorrow”

At the end, after four years of hearing his mother describe more and more horrors, never reaching the end of it, Guzlowski writes: “And I looked up and saw that she was about to tell me something so terrible that it would just about be the worst thing I’d ever heard, the last flash and stroke of lightning, and I said to her, ‘Mom, I don’t want to hear it.’ […] And she said, ‘Okay, you are 58 years old and still a baby, so I won’t tell you.” So, mercifully, we’ll never know that story. But there are plenty of others, reflecting her pain in pieces, like a broken mirror:

“Even when she had no more tears, she cried

cried the way a dog will gulp for air

when it’s choking on a stick or some bone

it’s dug up in a garden and swallowed.”

(“Grief”)

The inmates were dehumanized in the German camps, they became animals or plants: the mother – a suffocating dog, the father – “a bony mule with the hard eyes / one encounters in nightmares or in hell” (“What a Starving Man Has”). In Buchenwald and other camps, Guzlowski’s father and his fellow inmates were like mules carrying heavy loads, and dying of exhaustion:

“These men belonged to the Germans

the way a mule belonged to the Germans

and the Germans stood watching

their hunger and then their deaths,

watched them as if they were dead trees

in the wind, and waited for them to fall,

and some of the men did…”

While being tortured and abused, Guzlowski’s father thought of what he could not say to the inexplicably cruel guards: “Sirs, we are all / brothers and if this war ever ends, / please, never tell your children / what you’ve done to me today.” (“The Work my Father did in Germany”). He was right, they did not tell… Indeed, these crimes were largely forgotten, Germany was rebuilt with American help, while the German concentration camps were renamed “Polish concentration camps” in a revisionist twist, Goebbels-style.

Only the victims went on to continue carrying their war-inflicted trauma through years of hard work, drinking, quarrels, and sorrows of their exile in the new country, a country that they did not quite understand, nor belonged in. The lucid revelation of the war’s constant presence filling their souls with despair is one of the discoveries of Guzlowski’s book that may be perhaps the most difficult to bear: “my father is the corpse without lips,” “my mother […] bones and skin.”

“It has always been this way

and will always be this way.

War has no beginning, no end.

War is the god who breeds and kills.”

(“Worthless,” p. 137).

Modern positive psychology books talk about resilience and the ability to bounce back from trauma as an asset, an admirable strength of character that gives certain people “the Happiness Advantage” (a phrase from a title by Shawn Achor). Guzlowski’s parents did not have this advantage. Their deck of cards was stacked against them. They never recovered. Their son honored their memory by relentlessly recording their dark, dreadful days, their endless nights of drinking and arguing, the beating of their children, that passed on the pain from one generation to the next.

Intensely personal, the book is, at the same time, universal. Here’s the secret of Guzlowski’s impeccable use of language to capture the raw suffering of millions through the personal lens: “the bread of sawdust and sorrow…” “the scream that ends in screaming.” The book is an historical and literary revelation: when I first read it, I realized that I did not even remember how many millions of Polish slave laborers were feeding Germany and building up its infrastructure, the machinery of war. Bringing this experience home, through intense, starkly realistic descriptions of dire facts and brutal events, is one of the strengths of Guzlowski’s volume. It should be considered on a par with the work by giants of Holocaust literature – memoirs by Primo Levi, or stories by Tadeusz Borowski.

Guzlowski blogs about his parents and their lives and maintains a Facebook group recently renamed after the new book, Echoes of Tattered Tongues. If there was anything to criticize in the entire book, it is exactly this title, so difficult to say and remember. But, the stories it contains are equally harsh. At the end, this title is right, these are “tattered” memories – obscured, displaced, and gradually revealed, unfolding like stained bandages that cover a festering wound. We need to read this book today, in the age of needless suffering and endless war.

Guzlowski blogs about his parents and their lives and maintains a Facebook group recently renamed after the new book, Echoes of Tattered Tongues. If there was anything to criticize in the entire book, it is exactly this title, so difficult to say and remember. But, the stories it contains are equally harsh. At the end, this title is right, these are “tattered” memories – obscured, displaced, and gradually revealed, unfolding like stained bandages that cover a festering wound. We need to read this book today, in the age of needless suffering and endless war.

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!

That is how it was for so many of us.

When I was younger and my mother and me were alone my mother would start talking about this or that unpleasant experience during the war quite matter-of-factly no matter how terrible it was but you were never allowed to ask too many questions:- she shared only what she wanted to share from time to time and if you asked too many questions she would abruptly change the subject to the present, you were supposed to listen but not ask although I wish now that I had started writing these things down in a secret diary.

Often she would sit in her favorite sofa knitting and I would have my hands on her knees and stand there quite young having very grown-up conversations with my mother about things I could barely understand.

As she got older she tended to talk about these things less and less but when she heard about the war-reparations program being offered by Germany for former slave-labourers of the Third Reich she insisted on applying for it no matter how little they were offering.

However I had to question her closely and systematically about her time in Germany during the war and it became quite painful for her, like pulling teeth without anaesthetic, and finally she said “Już dość jest! but I had enough detail to write a good application and she got the money eventually.

It was painful for her to remember too much too quickly but I think also she just wanted to also protect us from too much emotional overload:- sometimes it could be very overwhelming for a small child to listen to all this death and destruction and your “fuses” would all “pop”.

In Communist Poland they erased us with their “politics of memory” and now in “Kaczpolska” they want to do it to us again but for us there was no “politics of memory”:- we got our Polish history straight from the people who helped to make it:- “Nie umierają czy których nie zapominamy!”

Polish Iliad

I sing of arms and a lost Polish tribe,

we who, exiled by fate, first came from the Kresy to Russian expanses

and then to Persia and the Holy Land and Egypt and to Italy,

and then to British shores and thence to many foreign lands, far and strange,

always to be strangers in many strange lands speaking languages not our own,

hurled about endlessly by land and sea,

and by the will of alien gods, and by our cruel neighbors’ remorseless anger,

long suffering also in war and in peace,

until we founded a city for ourselves

and restored our ancient traditions and rightful prosperity to our ancestral homeland,

Polonia, nobilia et serenissima.

Iliada Polskiego

Śpiewam o broni i zaginionego plemienia Polskiego,

my, wygnany przez los, pierwsza przyszliśmy z Kresów do Rosyjskich połacie

a następnie do Persji i Ziemi Świętej oraz Egiptu i Włoch

a następnie do Brytyjskiej brzegi, a stamtąd do wielu obcych krajów, daleki i obcy,

zawsze się obcy w wielu dziwnych krain mówiących językami nie jest to nasze własne,

cisnął o nieskończenie drogą lądową i morską,

oraz z woli bogów obcych, i bezlitosnej złości naszych okrutnych sąsiadów,

długie cierpienie także w wojnie i pokoju,

dopóki nie założyliśmy miasto dla siebie

i przywróciliśmy nasze dawne tradycje i prawowitego dobrobyt do naszej ojczyzny,

Polonia, nobilia et serenissima.

Interesting post – one slight correction ‘Nie umierają Ci których nie zapominamy’

Very well put. These memories do need to be recorded as much as possible lest we forget or have history repeat itself, as we are now seeing with Putin.

Pingback: Echoes of Tattered Tongues – Snowflakes in a Blizzard